TEEN DIVERSITY ESSAY CONTEST

2026 Contest Details

and Winning Essay Archive

The 2026 Essay Topic and How to Enter the Contest

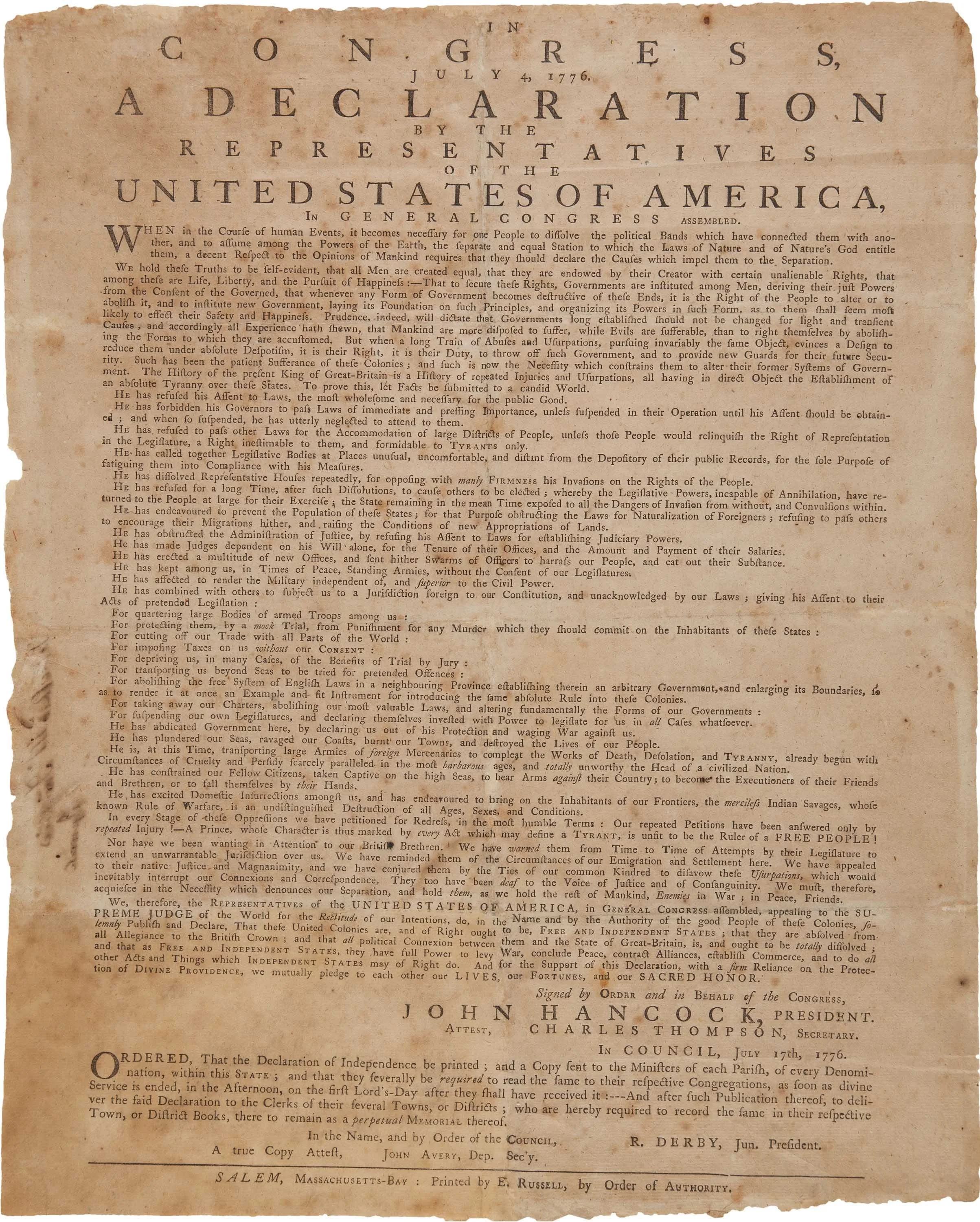

The Topic: The Declaration of Independence Challenge

The prompt for this year’s contest is as follows:

This year, the United States will celebrate the 250th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence, a document which Abraham Lincoln called “a rebuke and a stumbling-block to tyranny and oppression.” The Declaration of Independence was a product of its time, drafted to rally the colonists to defy Great Britain, support the creation of an autonomous and independent nation and attract allies to its cause. Nonetheless, its claims have been universalized and imbued with fresh meaning by people here and around the world who have regarded it as an enduring beacon of hope in their own work to seek equal rights, freedom and self-determination. The famous words in the Declaration’s preamble proclaiming as a self-evident truth that all men are created equal and have inalienable rights endowed by their Creator, including life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness have been widely employed to assert the inherent dignity and fundamental human rights of each person.

The Declaration of Independence is a foundational document in American political and social life that also inspires TEAM Westport’s mission: to build a community where diversity is welcomed, and inclusion, respect, and belonging are actively extended to all who live, work, attend school, or visit in Westport—regardless of ethnicity, gender identity, race, religion, and sexual orientation.

In 1000 words or less please comment on the following:

A) The relevance and value of the Declaration of Independence in your everyday life and your duties or obligations, if any, to uphold its principles for all people living within our democratic society; AND…

B) Opportunities, if any, you believe town leaders (including fellow students, school officials, community members and TEAM Westport) could create to act differently or additionally to reinforce the principles of the Declaration of Independence.

Submission Deadline: March 16, 2026

Awards Ceremony: April 28, 6 pm, at the Westport Library

Subject to the number and caliber of entries received, at the discretion of the judges, up to three cash prizes will be awarded:

First Prize:$1,000

2nd Prize: $750

3rd Prize: $500

The Teen Diversity Contest is open each year to students attending public or private high school (Grades 9-12) in Westport. Those who live in Westport and attend public or private high schools elsewhere are also eligible to participate.

Presented in partnership with the Westport Library.

The 2025 Teen Essay Contest Winners:

1st Place: Annam Olasewere

Understood. Connected. Valued.

2nd Place: Aanya Gandhi

White Paint and Other Lies

3rd Place: Souleye Kebe

S-L-M

Honorable Mention: Sienna Tzou

The Value of Identity from the Start

Click on the Archive below for the essays.

TEEN ESSAY ARCHIVE

-

CLICK TO HEAR THE ESSAYS

PROMPT:

TEAM Westport is dedicated to addressing issues of bias and discrimination related to race, religion, ethnicity, and LGBTQIA+ identity that negatively impact our town’s goal of being a welcoming community for all who live and work here. The recent introduction of the Anti-Defamation League's "No Place for Hate" initiative in Westport's schools strives to create an environment where all students feel they belong and are free from bias, bullying, or hatred.In our community, each person's unique identity – shaped by their race, religion, ethnicity, sexual orientation, and other aspects of who they are – contributes to the character of Westport. In 1,000 words or less, we invite you to reflect on how your own identity shapes your perspective and the experiences you have in Westport. Please address the following considerations in your response:

Which aspects of your identity feel most central to how you wish to be understood and accepted?

How do aspects of your identity shape your daily school and community experiences, including both challenges and opportunities in expressing these parts of yourself?

What specific changes could our community make to decrease identity-based bias, bullying and hate?

Understood. Connected. Valued.

Annan Olasewere

First Place

Growing up in Westport, I quickly learned what it meant to stand out. In a school of hundreds, I can count on one hand the number of students who looked like me. More often than not, it was just me-in classes, walking the halls, or sitting at lunch as the only girl of color in the room. Those moments made me more aware of the gap between how I saw myself and how I was seen by others.

Westport prides itself on being a welcoming community, but belonging is not just about physically being in a space with ochers-it's about being understood. It's about being connected to your community. It's about being valued. While I've never been directly told, "You don’t belong here," I've felt it in a thousand quiet ways-the double takes when I say Westport is my hometown, the disbelief when I step into leadership roles or excel in AP courses, or the doubt people show when I pursue activities outside the norm for 'someone like me'. It's not outright hate; it's something more subtle yet just as isolating-a quiet bias that makes me feel like I must constantly prove my worth.

And nowhere have I felt this more than in my sport. Fairfield County's athletic teams are known for their excellence-but not necessarily for their diversity. As a competitive swimmer, I step onto the pool deck knowing chat, more often than not, I am the only brown-skinned girl in the water. Even when I succeed, the reaction isn't admiration but disbelief-comments like, "How can, you possibly balance everything? The academics, the athletics, the extracurriculars?" No one asks others who succeed in multiple areas these questions. It's as if my accomplishments are unexpected, as though they were not supposed to be possible for someone like me.

Yet, despite these challenges, my identity has also been my greatest source of strength. Being different has given me a deeper sense of determination and resilience. I don't settle for less. I see the signs of bias now, and I don't lee them define me. Bue here's the thing-belonging isn't just an internal issue. It's also shaped by our structures and systems.

Westport wants to be a place where every student feels like they belong, but how can we when there are almost no role models and peers who look like us? Walking the halls, sitting in classes, and joining school activities, I rarely see faces that reflect my own. It's not just a feeling-it's a reality. African American students make up only 1.8% of the school district's population, meaning that in a graduating class of 400-500, there are maybe seven of us. Seven. Not in one classroom, not on one team-but in an entire grade. We aren't just underrepresented; we are scattered, spread so chin that it's easy co feel invisible. And it's not just among students. In a building with about two hundred educators, I can count on one hand the number of teachers of color. Five-maybe fewer. In all my years of school, I've never had a teacher who shares my background, who understands-without explanation-what it's like to walk into a room and immediately feel like an outsider. To be the only brown-skinned girl in a classroom, in an AP course, or on a team. To always feel like I have to prove that I belong.

Representation is not just a statistic. It's about walking into a space and seeing proof that you can thrive there-that your ambitions are not anomalies, and that you don't have to be the first one or the only one co be excellent. When we don't see ourselves reflected in leadership, in education, in success stories, we are left to wonder-do we truly belong here?

This isn't just an oversight; it's a missed opportunity. Representation matters-not just in the classroom, but in the way students see their futures. When teachers of color stand at the front of a classroom, they aren't just educators; they are proof that we belong in those spaces and that we can be scholars, leaders, and intellectuals. Westport needs to hire more diverse staff-not just to tick a box, but to show that they truly value all students and their experiences. While representation is important, the attitudes of educators also help unlock the potential students see in themselves. In my psychology class, I learned about implicit bias: how even well-intentioned people can unknowingly hold prejudices that affect their actions. Studies show that people can often-without realizing it-have lower expectations for students of color, are more likely to discipline them harshly or assume they need extra help (Quereshi & Okonofu; "Racial Bias"). This is not because they are bad people, but because bias is deeply ingrained in all of us.

This is why all teachers need to take implicit bias tests, not as an accusation, but as a tool for self-awareness. They need to recognize their biases, educate themselves, and actively work to do better. It's not enough to say, "I don't see color." Because the truth is, the world does. Pretending otherwise doesn't erase the experiences of students like me-it erases the chance to change them.

For me, Westport has always been home and I will always love my home. But home should be a place where you don't have to fight to fit in. It should be a place where no student ever questions whether they are out of place because of their identity. Where our differences are not just

seen but celebrated. Where the next girl of color walking into a classroom or diving into a pool doesn't have to wonder if she's the only one-because she won't be.

Westport is not a place of hate. But it is a place of gaps-of blind spots, of unintentional marginalization, of well-meaning people who don't truly understand ochers' realities. By sharing my story, I hope we can stare closing chose gaps and creating a community where true belonging means being understood, valued, and connected to those around you.

Works Cited:

Quereshi, Ajmel, and Jason Okonofua. "Locked Out of the Classroom: How Implicit Bias Contributes to Disparities in School Discipline." SSRN, 16 2 2024, Imps://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfin?abstract_id=4702736&utm. Accessed 17 3 2025."Teacher Racial Bias Matters More for Students of Color." NYU, 18 May 2017,

https://www.nyu.edu/about/news-publications/news/2017/may/teacher-racial-bias-matters more-for-students-of-color

White Paint and Other Lies

Aayna Gandhi

Second PlaceI used to believe that identity was something you could package neatly, something that could be shaped to fit whatever mold was required of you. After all, I had done it myself-layering coats of white paint over a canvas splotched in black, covering the parts that didn't seem to belong. A fresh coat each time the paint started to peel. A fresh performance each time the mask began to slip.

Moving to Westport was like stepping into a world that had already written its script. Individuality was celebrated, but only in its most polished form-never raw, never messy. There was a right way to be unique, a right way to be different. I learned early on that there were two versions of myself: the one that fit and the one that didn't. The one that could blend seamlessly into the rhythm of this town, and the one that pulsed just slightly offbeat.

Being a "hyphenated American" means existing in the space between the lines. It means translating parts of yourself depending on the audience, slipping between languages, between customs, between ways of thinking. It means carrying the weight of two histories at once, even when the world only asks for one. In Westport, I have felt this duality in ways I never had before. My roots extend far beyond the pristine lawns and quiet affluence of this town, but here, those roots are invisible. The fast-paced, electrified streets of India live in my memories, the rhythmic clatter of rickshaws and the rich aroma of spice stalls feeling like echoes of another life. But in Westport, there is no space for those echoes. Here, I am expected to exist in a singular dimension. To be American in a way that is digestible. Acceptable.

The challenge is not just being-different-it's being different in a way that others don't quite understand. It's the subtle mispronunciations of my name, the casual dismissal of my traditions as "exotic," the assumption that my heritage is an accessory rather than an integral part of who I am. It's the way my culture is celebrated when it's convenient-Diwali as an aesthetic, Bollywood as a novelty-but dismissed when it challenges the narrative of what "American" should look like.

I have spent years walking the tightrope between belonging and erasure. I have become fluent in the language of masking--of saying "I'm fine" when I'm not, of laughing off moments that sting, of folding myself into smaller and smaller shapes to fit the space allotted to me. But even paint has its limits. Even masks begin to crack.

There was a moment when I realized that the burden of translation should not fall on me alone. That my identity is not something that needs to be repackaged or rebranded to be understood. That my presence-unfiltered, unpolished-is enough. The true challenge of identity is not just existing within it, but demanding that others see it for what it is, in all its complexity.

Westport has the privilege of being a town that welcomes diversity in theory, but struggles with it in practice. The change we need is not just more cultural festivals or acknowledgments in school assemblies. It's deeper than that. It's in the way we teach

history-not as a singular narrative, but as a melting pot of perspectives. It's in the way we talk about identity-not as a checkbox, but as an evolving story. It's in the willingness to listen, not just to respond, but to understand.

I no longer wish to be understood in fragments. I refuse to be seen in halves. I am not just the parts of myself that are easy to digest, easy to praise, easy to fit into a pre-approved template. My identity is not something to be painted over, polished, or rebranded. It is vibrant, uncontainable, and wholly mine.

And for the first time, I am learning to stand in that truth-without apology, without translation, without another coat of paint.

S-L-M

Souleye Kebe

Third PlaceWhenever a person asks you who you are, the natural response is to give your name. What else would suffice as a distinguisher? From birth, it is the go-to summary of a person's identity. My name is Souleye, and for most of my life, I had no clue what my name meant. Turns out it's derived from Sulayman, which is translated into English as Solomon. Since my family is West African, we use many variations of Abrahamic names like Solomon, names that would be considered "exotic" or "peculiar" in the United States. I always took pride in my clearly African name, however, seeing it as a stronger distinguisher than the numerous Johns or James here. I always knew that I was Souleye Kebe, an African.

Being born an African, I had to come to terms early on that people who look like me haven't had a historically positive relationship with the United States. What made it easier was that I didn't have to accept that by myself, because I lived in New York City where everybody came from diverse backgrounds, many of them having similarly complex relationships with the country we were born in. Coming to Westport was admittedly a culture shock, since I had never seen so many people with such relative conformity. The students here had the same clothes, same style of speaking, and same style of general being. They also shared the same statements: requests like "Can I touch your hair?" remarks such as "I don't see color," and "boasts" like "I had a Black friend in elementary school." I thought that these words were nothing more than stories, and so I was astonished to hear people say them to my face. Through that, I remained Souleye Kebe, an African from New York City.

Despite me going to school here for three years, I still wouldn't rush to ever call myself a Westporter. I value my outsider perspective too much to seemingly diminish it with that title. I've found many outlets here to express that perspective, such as with my position on the Board of Education allowing me to filter the opinions of students and to discern which pieces of feedback best represent us as a school. These outlets, however, are more representative of my identity as it relates to attending Staples High School, and not of my identity as a "Westporter." These outlets make me Souleye Kebe, an African from New York City attending Staples High School.

When TEAM Westport asks students like me to propose specific changes to combat hatred and bias, I wonder why this burden of fixing systemic exclusion falls upon those already navigating its harms. The unabated truth is that it's not my responsibility, nor the responsibility of any other kid, to act as Westport's savior, driving it towards diversity and away from hatred. While I can and will support the town in any way I can towards that goal, it is incumbent upon the residents of Westport to seek that change for themselves. Every person must look inward and examine their own potential predispositions and immediate judgements, determining for themselves whether they want to put the effort towards a more kind and tolerant Westport. We can mold students towards that mindset by implementing diverse thought processes in all parts of their education, showing them that the world they live in is a mere slice of true reality, and is not reflective of how diverse the world truly is. However, we can't force them to make a positive step, it's entirely on them.

Living here, I see my identity spread between the two continents of America and Africa. The distance between these two places has made me realize that I am in truth a child of the world, as all people are. We often forget how we are all inhabitants of the same planet, being too caught up in the immediate to notice. We think and say disgusting things to others outside of our close proximity because the distance protects us. This is not a proper way to live. I doubt that I would subscribe so fully to this realization had my identity not been spread as far as it has, had I not been afforded this perspective uncommon to the people of Westport. While I think this perspective is a strong impetus towards global thinking and away from prejudices and bias, it is incumbent upon the Westport community to carry that energy forward.

I will not tell this community the minutiae of every step they need to take to make Westport a more welcoming place, the town must first see for themselves the peace that can be made and that can exist by celebrating diversity and opposing hatred. Look at the names of the people of the world. My name as well as its many variations are all derived from the triliteral root S-L-M. We hear it in Salam and in Shalom and in Solomon and in Shlomo and in Sulayman and in Souleye. This root mea!ls peace, which is something we can all strive for. My name is Souleye Kebe, an African from New York City attending Staples High School, who is working to be an advocate of peace.

The Value of Identity from the Start

Sienna Tzou

Honorable MentionBy the first hour of my first day of kindergarten, I had heard "Say 'hi,' Sienna" from my mom about a hundred times.

I stood behind my teacher when she introduced me to the class. I ducked my head, stared at my shining, coruscant ballet flats, and whispered as feebly as possible, "Hello."

That was the only word I knew in English.

I saw that some of my classmates snickered and very audibly attempted to imitate how I spoke. Others whispered and pointed their fingers at me, as if my Asian "exoticism" was a foreign contaminant that could somehow infect the class.

For the next two years, I made a silent resolve to avoid socializing altogether. I didn't want kids mimicking how I spoke, and it gave me the excuse to not be obligated to answer the unfiltered questions I knew everyone wanted to ask me.

By the third grade, groups of girls were impersonating me by blabbering gibberish as my Mandarin, and pulling at the corners of their eyes behind my back.

Thus, I forced a stoic, protective facade over my true identity, shrinking back into a silent reticence of social evasion.

This does still linger with me to the present day, for I do have a more indrawn nature and very often prefer solitude over intimacy.

This is not to say that I am solely a victim of prejudice and acts of hate. There was once a very apprehensive, timid Black girl in my second grade class. Many times, when our teacher was not paying attention, agroup of White girls would pour scorn on her for trivial matters.

Knowing that I was quiet and docile as well, they told me to do the same. I did feel inclined to, because it was one of the few opportunities I had for societal acceptance.

Yet, I knew that there was a fundamental insecurity that the girls were projecting onto the timid girl. I was young and didn't exactly know what it was, but I knew that demoralization was wrong.

She was exactly like me. She never spoke a word, but I knew we had so much in common. We were both afraid to speak out because we were different. \Ve feared that saying something would get us further rejected and criticized.

So, I decided to befriend her. What would it hurt? I didn't have any other friends and, if anything, we could come out of our shells together.

In the end it didn't matter, and our friendship didn't last, because she didn't last very long. She and her family subsequently left the town or moved schools-I don't know where life took her. I don't think I ever will.

Already, as a young child, I knew that the community had an ingrained difficulty accepting people like me of a minority race. With White being the majority race, it was an inexorable curiosity that the youth would eventually weigh up: Was there room for kids who were "different"? Did we even belong here?

Young children may just be curious, but they are much more susceptible to bias or oppose those from various ethnic backgrounds, or those that are visibly different from everyone else. Neutrality is not always in their disposition.

Although, I will say, hate, bullying, and prejudice happen to be much less prevalent in the higher grades.

The reason for this might be higher stakes that have been implemented to breaking rules of conduct against discrimination of race, religion, sexuality, etc.

However, we must not forget that growing our youth properly is vital for the flourishing of the individuals and young adults that we will become.

From the start when a child feels out of place, it molds their personality and their perspectives on their individual lives differently. Almost invariably, being shunned at a young age by peers can have a lasting residue on one's dignity and inherent qualities.

To prevent the silence of minority voices, we must raise them from the beginning. Children that enter kindergarten or new schools are often shy and unsure of themselves, which is a rational fear. Cliques start to be made after introductions-especially those who are inherently a bit more extroverted than others.

Coming from someone who, as a child, just missed the train to be in any closely-knit clique, this is probably the most essential part about a kindergartener's experience.

Bonding activities can be administered to implement more inclusivity. For instance, random pairing with a buddy, class matching activities for similarity, and writing notes to classmates that compliment their unique and likeable qualities can all build rapport over time.

Besides classroom engagement, primary schools can have guest speakers discuss the benefits of inclusivity and how to speak up from identity-based bullying or bias.

The community in general can also practice accepting unique qualities as special and welcome. This may contribute to more meaningful and sustainable connections, which is indispensable for our town's youth.

Each person in this town deserves to get their voice heard. Those that have contrasting races, religions, or identity orientations are distinct, but not incompatible-we just need to be more accepting and see the different as people we can thrive and grow our youth with.

As I have grown into an adolescent, nevertheless, my morale has been augmented so that I can be the individual I am today. I take pride in the fact that I get to live with so many perspectives to ultimately mold me into an empathetic and discerning adult. I'm looking forward to the day where I can call myself that.

I am, of course, proud to be part of this community with exceptional education and boundless opportunities. I just do wish I could go back in time and adjust my younger self to be a more confident being.

I wish I could tell that girl with the shining, coruscant ballet flats and a dimpled, cheeky smile that everything you have to say is valued and the world is waiting for your worth to shine through.

-

The regulation of hate speech must balance limiting speech that may be considered offensive, threatening or hurtful with the constitutional right of free expression.

In 1000 words or less, with respect to speech that targets specific people or groups based on race, religion, ethnicity, and/or LGBTQIA+ identification, consider the guidelines one should set for themselves within Westport’s schools and in our community. Explain how a diversity of opinions can be safely and respectfully shared. Are the rules different in a school community than on social media?

Sophia Lopez: Westport’s Contest of Conformity (1st place)

In a world increasingly connected through technology and social media, the power of speech has never been more apparent—or more fraught with consequences.

In Westport, a predominantly white town where societal norms often dictate conformity, it is imperative to establish clear guidelines to ensure that all voices are heard, respected, and valued.

Our own must prioritize inclusivity and respect in schools and broader community interactions like social media. To achieve this, several key strategies must be implemented from day one.

As a child with a multitude of thoughts and unique characteristics and ways of expressing them, I quickly discerned that I was an outsider in my community. Despite my best efforts to assimilate and conform to societal expectations, I could never fully escape it.

As early as Kindergarten, I experienced the profound impact of feeling like my voice was not valued in my community due to the factor of race. Kids ridiculed me because I looked and acted differently from the majority.

In 2019, the Hispanic population of Westport was around 4.5%. In 2012 when I was in Kindergarten, the population was even lower.

I didn't understand why my dad had never come to a “back to school night” after my first one.

Being a Spanish immigrant, he didn't feel comfortable enough to. I was mad at him for this.

In this contest of conformity, nobody cared what type of brown you were, and you would be naive to believe they would remember. At my white friends' houses, every aspect of my personality that wasn't common stood out immensely, making me feel unwelcomed.

Other times, I felt my existence was only to take the purpose of a pawn. I felt like an abnormality that was on display for show and tell. My insights had become unnecessarily amplified because of my identity.

I remember coming out in the 7th grade. Girls I had never talked to messaged me to congratulate me. I was one of the only openly LGBTQ+ people in middle school and I believe they wanted to convince themselves that they were supportive, so they forcibly associated with me.

Instead of making me feel empowered, that silenced me more. Some of the most vile people I have ever met would have those signs outside their door saying they stood with me.

With rainbow flags raised, they declined the sleepover invitations purely because I liked girls.

Sometimes, it came passive aggressively during a dinner-time conversation. “Sophia, you’re young. You don't know anything about your sexuality or who you are as a person.” They felt so proud of themselves after saying that, too, as if they had just killed the disgusting beast which was my homosexuality.

If I had the opportunity to banish it, I would have done so as soon as people started seeing me differently. We cannot let our children grow up with this mindset.

What is a community without diversity?

Let's not forget Westport’s emphasis on academics. In no way am I ungrateful to be here, but I do want to point out that the stress on academics here can further contribute to a sense of alienation which further leads to hate speech.

Despite having valuable insights, my worth was measured solely by academic performance. Throughout elementary school, I had gotten the highest state test score possible.

During middle, as my mental health worsened, so did my grades. Nobody asked why; they just jumped to conclusions. Constant labels given to me stunted

me even more. “Burn out.”I wish someone had sat me down and asked why instead of rapidly judging me based on a percentage or letter grade early on. I wish I could’ve sat her down and

told her she was worth more than that.If we want to reduce hate speech, we must welcome empathy and compassion.

So, with these ideas in mind, how can one be a good person while still being honest and up front about how they truly feel?

First, measures must be taken to address the inherent biases and societal pressures that exist within Westport's culture. The town's homogeneity and

unintentional emphasis on conformity can create an environment where those who do not fit the established norms are marginalized or targeted. Even today, I wonder what it would be like if I

grew up in the way that most did here.While I have made peace with my differences, it never fails to upset me thinking about my younger self that hated what she saw.

Westport has to stop being scared of accepting the fact our youth may be dealing with the same thoughts. Initiatives such as multicultural events, guest speakers from diverse backgrounds, and an inclusive curriculum can broaden perspectives and foster a more inclusive community. Encouraging curiosities and question asking is a must.

In addition, it is also crucial to establish clear guidelines for respectful communication and discourse. Both in schools and on social media platforms, individuals should be held accountable for their words and actions. Schools also need to be held responsible for upholding their codes of conduct that emphasize consequences for harassment or bullying.

However, it is important to recognize that the rules for communication may differ between schools and social media platforms. While schools have a responsibility to maintain a safe and inclusive learning environment, social media operates within a broader context where freedom of speech is valued.

Nevertheless, both environments should uphold principles of

respect, empathy, and tolerance.I realize that my experiences are not unique and that many individuals face similar or more extreme challenges here or all around the world. However, it is essential to recognize the inherent value of diversity and to create spaces where all voices are heard, respected, and valued.

By fostering inclusivity and embracing differences, communities can empower individuals to embrace their uniqueness and contribute meaningfully to our community. When children feelsafe enough to encourage and not conceal their differences, only then will we have a community where every voice is truly valued and celebrated.

Olivia Morgeson: "Hate Speech Has No Home Here" (2nd place)

Hate speech does not allow for a diversity of opinions. When someone mocks your very being, they’re not looking to share their opinion and hear yours. They’re not seeking to learn. They’re looking to hurt.

But how does one define hate speech? For example: Is it hate speech when my classmate tells me to “go back to China”? This comment made me feel anxious,

embarrassed, and alienated; but it did not make me feel unsafe.It’s an ignorant statement. It’s nonsensical. But it does not pose a threat to my well being.

When I read about last month’s Board of Education meeting concerning racist behavior at school, my mind went to two places.

Firstly, I felt great empathy, because I unfortunately could relate, and knew all my non-white friends could relate too. It’s the common minority experience in a white town: receiving unsolicited, abrasive, racist comments at a young age.

We encounter racism so early on that sometimes it’s before we know what race is. My first experience being called a racial slur was when I was in first grade.

Secondly, I was completely taken aback by the specifics, because while I could relate to the disrespectful name and slur-calling, I have never experienced threats of targeted violence. While hate speech has no consistent definition, it is often described as threatening speech expressing prejudice. So perhaps I wouldn’t consider “Go back to China” hate speech.

But if it were to be, “Go back to China or I’ll hurt you," then that would be a different case.

A student took a photo of a black student and said, “There’s about to be a hate crime." I cannot possibly see how this could be interpreted as anything but hate speech; a threat to the safety of a child on the basis of race.

When a person is found guilty of assault, they receive a penalty. However, if it’s

discovered that the assault was targeted due to the ethnicity, religion, or sexual orientation of the victim, the penalty is increased.ncidents of hate speech at school must be approached with similar severity; if we are to adequately prepare our children for the real world, this principle must be mirrored and applied within our school system.

Children are impressionable and lack maturity. They are, however, also capable of growth. Therefore, punishment should be accompanied by proper education. Harmful behavior must not be excused and actions should not be forgotten; yet, it must be followed by education.

Without education, any punishment is meaningless; without education, the student will not be given the opportunity to learn and grow as a person; without education, the student will move on to another target.

Thus, it’s important to directly combat any ignorance by detailing why their words are harmful, why they received any punishment, and why they must learn to treat others with proper respect.

It’s less challenging to determine the consequences for students who use hateful speech than it is to determine how the pain of the victims can be alleviated. How can a community as a whole go forth when students are repeatedly disturbed by the cacophony of hate speech?

There is no solution– there is an aspiration. Minority children must remember that they are not at fault for others’ wrongdoings, and that they are unconditionally accepted.

They must also understand that they are not alone, that this is a common experience, and that there are pockets of the community built upon empowering one another.

There were several comments on articles concerning last month's Board of Education meeting that intrigued me, but one stood out in particular: “A sign ‘hate has no home here’ on a lawn looks great, [but] are we as a community preaching and practicing this in our own homes?”

It’s important that Westport families strive to raise their children knowing not to

discriminate and not to threaten violence.Moreover, it’s crucial to provide strong guidelines for hate speech at school and community assurance that all individuals are welcomed and protected.

Only then can the entire community flourish as a center of education and respect.

Only then can it be possible for the “common minority experience” in Westport to not be common anymore.

Teya Ozgen: "Do Schools Suppress First Amendment Rights?" (3rd place)

Children are curious.

At a young age, children want to know things. In elementary school, instead of Lunchables or peanut butter and jelly sandwiches, I brought Chinese dumplings and noodles. Some kids would ask “Hey, what do you have for lunch? I’ve never seen it before, could I try some?”. These comments made me glad to share my culture. I have always been proud of being Chinese.

Other students would make snide remarks. “What are you eating? Eww that smells! Is that dog?” These comments would make me hide my food and wish I could disappear.

These comments are not illegal. However, in schools where students learn and grow, hateful comments have no place.

School administrators are trained to protect victimized students and de-escalate difficult situations. But sometimes situations aren’t as they appear.

Last year, a neuro-diverse student, looked at me and yelled “Not all people in America are the same," pointed at me, and screamed “Asian."

I did not know how to react, so I laughed as a coping mechanism. Laughing was better than crying. The whole class started laughing too. I couldn't tell if they were laughing at her, laughing with me, or laughing at me.

My teacher did not hear the exchange, but assumed I was making the whole class laugh at a neuro-diverse student. Even after explaining the situation, my teacher felt the need to protect the other student.

After feeling victimized by the class, I felt doubly victimized by my teacher. I tried my best to explain what happened; however, I was not in the best mind space to defend myself.

In situations like these, I hope that teachers can work to understand nuanced dynamics in the interest of protecting all students.

Asian hate is often disregarded and not taken seriously because Asians fit the model minority stereotype. “Oh you got a 97 wow! But you’re only smart because you're Asian!” I have heard this so many times as a joke or a compliment.

In reality, all racism is hate, and freedom of speech that is hateful violates

other people’s rights.Rules in schools must be stricter and protect students. There is a stark contrast between a diversity of opinion and hateful speech. Though freedom of speech is a right exercised from the Constitution, hateful words have no place in the Westport Public School district.Within our community, it is necessary for individuals to take it upon themselves to protect students of different races, religions, and identities. The term “casual racism” is often used to describe micro-aggressions that can be easily disregarded.

Racism is never casual, and we must protect everyone in our community. Many of my peers have undergone racist situations, and have not felt the comfort and security from our administrators enough to speak up. The job of educators is to not only teach, but to also make students comfortable enough to stand up for themselves.

Even personally, I have experienced racism as an Asian-American who has been in Westport Public Schools since kindergarten. Some incidents I have reported, others I haven’t.

Either way, I have never felt fully supported and comfortable enough to open up about the hate I experience.

Freedom of expression is strictly dictated in the First Amendment. However, many rules in school do not strictly follow the Constitution. In school, you may not dress inappropriately, you may not use profanity, and you may not skip classes and congregate in the halls.

All of these rules are implicated for important reasons; however, they test the boundaries of the First Amendment. The dress code is necessary: Students should not wear inappropriate clothing in a learning environment. However, doesn't the dress code suppress students’ right to express themselves freely through clothing?

The banning of profanity violates Freedom of Speech; the banning of congregating in the halls violates the Freedom of Assembly.

Constitutional rights cannot exist without some restrictions. Diversity of opinions are orthogonal to hate. Difference of opinion can be respectful and educational.

In contrast, hate speech is used to bring down others for differences they can not control. If you believe in a different religion, you can still have a passionate but respectful debate, but this requires that schools provide a safe and respectful

space for students to express a difference of opinion.If you make antisemitic comment, that has malicious intent. That is not freedom of speech and should be punished and prosecuted in our school district.

On social media, cyberbullying is common. Many do not care about digital footprints and unleash obscenities at other people. Online, there is the false protection of anonymity. It is easier to hate on a username than a real human face.

On social media, people are often much less restricted than they are in real life, especially in a school. Easy access to technology and a mindset of “Oh I’m just joking, it's not racist” is a combination leading to the spread of hatred.

Whether it be comments directly at you, or hateful content consumed by the media, racism gets more normalized daily. Social media must be consumed mindfully. As active users of technology, people must think critically before putting hate onto social media.

Freedom of speech is exercised much more dramatically online because of the ease and accessibility of social media. We must keep in mind positivity and the absence of hate when as users.

In conclusion, schools must be meticulous when protecting students against hateful speech. Freedom of speech and expression can not be fully exercised in a public learning environment.

Difference of opinion can be expressed without hate when all people involved stay respectful. It is incredibly important to be mindful about malice on social media, because it spreads more easily and freedom of speech is not regulated.

We can all express contrasting ideas, without the presence of hate and hatred. Disagreements do not have to lead to bullying, racism, homophobia, or discrimination.

-

Team Westport’s mission is to make Westport a more welcoming community with regard to race, religion, ethnicity, and LGBTQIA+. In order to achieve its mission, one of TEAM Westport’s goals has been to promote opportunities for people to come together in dialogue to better understand each other’s experiences, decrease bias, and learn what we have in common. Meaningful dialogue depends on a good faith effort to set aside preconceived beliefs or what we think we know about other people.

In 1,000 words or less, reflect on your own interactions with people who have different racial, ethnic, religious, and/or LGBTQIA+ identities and/or perspectives. What kinds of conversations were particularly helpful in prompting you to rethink your beliefs or opinions, perhaps causing you to change your mind or enabling you to better understand others’ points of view? Based on these experiences, what specific actions would you suggest that individuals, schools, and/or town entities in Westport take to promote good-faith dialogue, reduce bias, and foster understanding?

ANNIE DIZON: POWERPOINT AS PRIDE (1ST PLACE)

Ang sakit sa kalingkinan ay ramdan ng buong katawan.

The pain in the little finger is felt by the whole body.

I could feel every fiber of the blue fluffy carpet scratching on the back of my legs, the chattering and fidgeting of my fifteen classmates surrounding me. Pinching the loose skin between my fingers to calm myself (to no avail), I watched anxiously as my dad worked with my teacher to set up his presentation on the SMART board.

I wanted to throw up.

I was in third grade, and each week a family member of one of my classmates — a parent or grandparent, an aunt or great uncle — had come to give a talk about their family’s origins in the United States. Each week was the same story: the Italian or Irish or English family that went through Ellis Island and settled across New England, building its wealth over generations to end up in its present-day privilege palace.

But my family’s story was neither as simple, nor as old. In 1979, my dad, his three older siblings, and his parents fled the Philippines in the wake of political turmoil as president-turned-dictator Ferdinand Marcos began taking over the country under martial law.

They settled in a three-bedroom apartment on the second floor of a dilapidated complex in San Francisco. But at the time, I barely even knew these facts. My only conection to a sense of the identity my father and I shared was a mutual hatred towards our aunt’s ugly toothless chihuahua and a love for lumpia.

I did not know that my father, a threadbare backpack strapped across his scrawny shoulders, worked inglorious part-time jobs after long school days. That my grandma traded in her aproned housewifery for 12-hour shifts in the basement-turned-sweatshop on the corner of 28th.

Or that my grandfather gave up his passion, teaching, and took work as a school janitor, mopping sweaty gym floors and dimly-lit locker hallways at night, haunted by gum tucked under the desks of empty classrooms and with only ghosts to fill the chairs for his late-night lessons.

So as I sat watching my dad set up his presentation, I knew I needed this to be perfect. I felt as if everyone was expecting my dad’s presentation to be something new, something unlike the other stories of European immigrants they’d seen before, for one sole reason: we were different. I was the only Asian, the only minority, in my class. If I thought it was bad that I barely knew anything about my Filipino heritage, my peers’ lack of knowledge about Asian culture was a travesty. I needed this presentation to explain our culture, our ethnicity, why it was important, the questions I didn’t have answers for. I needed this presentation to make sense of the why, for what reason my eyes slanted a little bit more downward and my skin was a little bit more tan than those of my classmates.

And I believed my dad was not going to be any help. I thought he would have two photos and a dumb story about Grandma, and everyone would get bored, annoyed that they had to sit through a presentation about a different kind of immigration story that wasn’t even relevant to what we were learning. They’d think it was unimportant, unnecessary to learn about, a lesson with nothing of value, and they’d take their frustration out on me. I could barely accept my own differences as something of worth. What would it mean for my existence in these white spaces I desperately tried to fit into, if my dad’s presentation tanked and that sense of inferiority became my reality?

The SMART board turned on. The screen flickered with a soft blue light, gaining in vibrancy as the projector stuttered alive, the machine filling the room with the sound of its quiet whirring.

It was a picture of Bruno Mars. Everyone looked at each other, confused.

“Do you kids know who this is?” he asked. A few kids raised their hands, not quite sure if this was some kind of trick question either.

He pointed toward one towhead blond boy in the group. “Bruno Mars!” the boy shouted.

My dad nodded approvingly.

Next was a photo of Vanessa Hudgens.

“Do you know what these celebrities have in common?” he posed. There wasn’t as much of a response.

He gave a coy smile. “They’re both Filipino.”

My dad continued, displaying pictures and information of the vibrant, bustling cultures of the Philippines. He told the story of my family’s immigration, of the trials they all faced that I hadn’t even known. He talked about the diverse range of ethnicities, foods, and religions, and the deep-rooted love Filipinos hold for boxing and basketball. By the end of it, everyone was laughing, entertained by the captivating presentation they had just witnessed. They all knew it was the best they’d seen, better than any other of the drawn out, dead presentations made by the other kids’ stuffy white grandmas. My dad’s presentation on the Philippines, my heritage, was more entertaining, more captivating, more fascinating than anyone else’s, and everyone knew it.

This was the first time in my life I’d felt something other than shame about being Filipino, an invisible guilt to everyone’s eyes but my own. That morning, my dad planted within me the seeds for something I had never felt before, something that, not without its setbacks, has slowly sprouted throughout the years: pride. My dad taught me that there is strength in my differences, that there are blessings, power, and love beyond belief in the stories of the people who came before me. I have learned that what sets me apart from others is not a kind of weakness, and it is with that fact that I will continue to live with pride. Because, as the saying goes:

Ang hindi lumingon sa pinanggalingan, hindi makalcarating sa paroroonan.

A person who does not remember where they came from, will never reach their destination.My dad continued, displaying pictures and information of the vibrant, bustling cultures of the Philippines. He told the story of my family’s immigration, of the trials they all faced that I hadn’t even known. He talked about the diverse range of ethnicities, foods, and religions, and the deep-rooted love Filipinos hold for boxing and basketball. By the end of it, everyone was laughing, entertained by the captivating presentation they had just witnessed. They all knew it was the best they’d seen, better than any other of the drawn out, dead presentations made by the other kids’ stuffy white grandmas. My dad’s presentation on the Philippines, my heritage, was more entertaining, more captivating, more fascinating than anyone else’s, and everyone knew it.

This was the first time in my life I’d felt something other than shame about being Filipino, an invisible guilt to everyone’s eyes but my own. That morning, my dad planted within me the seeds for something I had never felt before, something that, not without its setbacks, has slowly sprouted throughout the years: pride. My dad taught me that there is strength in my differences, that there are blessings, power, and love beyond belief in the stories of the people who came before me. I have learned that what sets me apart from others is not a kind of weakness, and it is with that fact that I will continue to live with pride. Because, as the saying goes:

Ang hindi lumingon sa pinanggalingan, hindi makalcarating sa paroroonan.

A person who does not remember where they came from, will never reach their destination.

TYLER DARDEN: AMERICAN BOY DOLL (2ND PLACE)

When I was a child, my mother took me to the American Girl Doll store in New York City. I remember my excitement at walking through the store, seeing all of the stylish dolls lined up against the walls, and propped up on the tables. I wandered around for a while, scrutinizing every doll until I found the one: She had wavy brown hair that cascaded down her back, and she wore a vibrant blue sundress. I could not wait to show her off to my classmates; surely they would admire my doll as enthusiastically as I did.

I proudly carried my doll into school the next day, anticipating my peers’ faces when I introduced her to them. However, it didn’t go as expected. The boys glared at me like I had done something wrong, and the girls served up some serious side-eye. What I thought would be celebrated, was condemned, like a dog presenting a dead bird to its owner. I felt ashamed for bringing her, and from then on, I neglected my doll.

Even though I was young, I began piecing together what it meant to be a boy.

Boys are strong, fearless, brave, tough, and confident — but I was none of those things. Boys like girls. Boys are not supposed to like other boys — but I did. I was not “normal,” and the shame that came along with that would plague me for years. I did not feel comfortable in my own skin, and I could not be honest about who I was. I kept the world at an arm’s length.

Despite my internal struggles, there was hope: my mother. She had always known that I was different, and she loved me no less. I clearly remember her telling me, “If you want to be a ballerina, I’ll buy you a tutu.” She always tried to find ways to let me know she was, undoubtedly, in my corner, yet, I was consumed by shame. I kept the seemingly simple words “I’m gay” in the recesses of my mind.

After investing in my own personal development, I was able to cultivate a sense of self-love and self-confidence. However, it took a lot of time and hard work. I went through many treatment programs and worked with many therapists to come to terms with the root of my discomfort: fear that my sexuality wouldn’t be accepted.

I realized I could either let shame destroy me, or I could trust that people would love and support me, regardless of who 1 am or who I love. I came out to my mom knowing that she would embrace me, but I was still weak with fear.

“I’m gay,” I said. Those words had been sitting in my mouth for a long time and now they were free, floating in the air between us.

My mother smiled.

“I know,” she replied warmly.

The pure relief I felt is indescribable. All that I had been feeling faded like the outro of my favorite song. I was finally able to be myself.

I often reflect back on that carefree day as a child in New York City. I had not (yet) been affected by traditional gender norms or what it would mean to be different. I was simply excited to buy a doll and share her with my classmates. My mother was equally as excited, she only wanted me to be happy. How different things could have been for me if there had been any open discussion about sexuality and breaking traditional gender norms. Having those conversations could have helped to foster understanding and acceptance for people like me.

How can I possibly conclude this essay? It’s hard to suggest what can be done to foster acceptance when I have only recently come to terms with my truth, and shared it with others. However, I do believe I can offer a pearl of wisdom based on my experiences in (what I found to be) traditional and confining school environments.

I believe elementary schools should be the first step in introducing the concepts of diversity and inclusion. This can be done through simple things, like sharing picture books and creating art projects that express differences. In middle school, a time when kids are beginning to understand themselves a bit more, it is crucial to allow them the space to discover who they are without imposing societal norms. This may be through class discussions which explore topics like identity and non-traditional gender roles. High schools have the opportunity to create safe spaces for students through clubs and special events. This may be helpful to people who are questioning their own identities or simply hoping to show support to their peers. The earlier these concepts are introduced, the less taboo they become, and the more we encourage overall understanding.

I understand the toll suppressing one’s sexuality and conforming to traditional gender norms takes, and I empathize with those who are not yet out. I hope that people, no matter their identity, acknowledge how much courage it takes to reveal one’s true self. I believe if schools counteract the beliefs that society has etched into our minds, perhaps others will not succumb to feelings of shame.

SAVVY DREAS: LEARNING THROUGH OUR DIFFERENCES

(3RD PLACE)

Throughout middle school, I attended several Mosaic conferences centered around diversity and understanding our intersecting identities. Before these events, I had never encountered the phrase “socio-economic status” or thought that a history class could have a bias. These meetings never failed to leave me with a whole new perspective on my life and the lives of those around me through meaningful conversations, silent activities, and deep listening.

Hundreds of kids came from schools all around Connecticut creating the most diverse group of people I had ever been surrounded by at that age. However, instead of feeling overwhelmed or uneasy like many people express in uncomfortable situations, I felt an immense sense of love and camaraderie. When people chose to share an experience the room fell silent with admiration and respect for the speaker. Everyone belonged and didn’t belong all at once.

I vividly remember one girl about my age sharing her experience of the way race shaped her identity in a predominantly white school. I had never considered the possibility that someone had to think about or change the way they acted to feel a sense of belonging in a community.

Growing up white, I never had to think about race or privilege. This idea was intensified when I participated in a privilege walk for the first time. A speaker called out prompts relating to a multitude of identities like family make-up or racial experiences and people stepped forward or backward depending on what they identified with. Acknowledging where I stood in contrast to my peers, I recognized my privilege for the first time. After this experience, I started reading a lot of books regarding the history of minorities and biographies about growing up as a minority whether that be race, gender, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, or disability.

I wanted to better understand what I could do with my privilege. That’s when I discovered the term anti-racist. The idea that just being an ally isn’t enough, but that racism and discrimination in this world require active resistance, this understanding was reinforced when I attend SDLC during my freshman year.

Despite being over Zoom, I felt the same kind of love in the break rooms and meetings. One of the most groundbreaking things I learned that week was about the underlying racism of our history curriculums, specifically the map of the world.

At that point in my life, I was confident that this mage was fundamentally engrained in my brain, so nothing said about it would change much for me. that was until the speaker pulled up another map right next to it with completely different proportions.

I sat there totally confused. Those two images were both of the world, but the one I was not familiar with had Africa and Asia drawn as much larger parts of the picture. The speaker then explained that many textbooks skew maps to make the United States seem like the center of the world, when in reality it only takes up a small fraction of it. I could not comprehend the fact that something I had been taught and shown over and over again was inaccurate and more alarmingly, racist.

This moment sparked a change in me that led to several conversations with my head of school about the history curriculum and eventually directed me to the Tulsa Massacre. When I first heard about it, I was certain that it could not have happened in the United States. In my naive thinking, I could not fathom that one of the largest racial massacres in the world happened in Oklahoma, yet was not mentioned once in any American history course I had taken.

My grandmother at the time lived in Oklahoma and taught in high school. I brought up the Massacre to her, hoping I would find more insight but was shocked to learn that she had never even heard of it. I didn’t really understand how a group of people could be silenced or have their history erased until that moment. Although it was only one event it opened my eyes to so many of the other discrepancies and biases in our everyday lives, both conscious and unconscious. Events like these are part of the underlying causes of the racism and tension in our country today and it is through educating ourselves on the history of our privilege and the past that we can try to make a small step forward.

One of the biggest drivers of change needs to be the ability to listen to one another in an open-minded and inclusive space. While affinity groups are incredibly impo1tant for allowing people to communicate their shared experiences, we need spaces for people of all backgrounds to be involved in open dialogue around diversity. Most people are unaware of the daily struggles others face and without acknowledgment, there cannot be progress. One of the things I loved most about the diversity conferences is that I got to learn through my peers about what they experience and what I can be more aware of. Through this space, all students interested in diversity work can have thoughtful discussions about uncomfortable or stigmatized topics to foster growth and understanding in our communities.

From a school and town position, we need to reiterate the importance of diversity conferences and interactions with people different than ourselves. There need to be more school assemblies about identity and the way it shapes people’s lives. Private schools, specifically, tend to avoid those topics out of fear of offending someone. However, if we live in a place of fear instead of a place of growth nothing will improve. Designating assembly times for speakers of different backgrounds can be a critical step in developing a community of respect and understanding. Education should be at the forefront of reducing bias and fostering understanding within our own communities.

-

“Why can it be so difficult to talk about race?” Trevor Noah, award winning comedian, writer, and television host from South Africa, says, “... the first thing we have to do in any conversation is figure out what the words mean in the conversation that we’re having.”

In 1000 words or fewer, describe what you would like to explain to people in your community who avoid or struggle with talking about race or acknowledging systemic racism or who apply a "colorblind" approach to issues.”

First Place: Ian Pattan with "How to Be a Good White Person"

Second Place: Colin Morgeson with "Villains of Our Stories."

Third Place: Leigh Foran with "Embracing Privilege to Tackle Racism"

-

The statement “Black Lives Matter” has become politicized in our country. In 1000 words or fewer, describe your own understanding of the statement. Consider why conversations about race are often so emotionally charged. Given that reality, what suggestions do you have for building both equity and equality in our schools, community and country?

First Place: Max Tanksley with "Words of Power"

Second Place: Curtis Sullivan with "Black Lives Can Matter More. Here's How."

-

First Place: Sahiba Dhinsa with “Stereotypes, Stories, and the Worlds We Create”

Second Place: Zachary Terrilio with “Stereotypes: Crippling Standards”

Third Place: Victoria Holoubek-Sebok with “Bombshell”

-

First Place: Chet Ellis with “The Sound of Silence”

Second Place: Angela Ji with “Stereotypes: Crippling Standards”

Third Place: Daniel Boccardo with “Cactus in a Rainforest”

-

The focus of this fifth essay contest is the issue of “appropriate protest” which has surfaced recentely as a topic of significant national controversy. This year’s invitation states, “Recently several professional athletes have “taken a knee” during the singing of “The Star-Spangled Banner” to bring attention to— and to protest— ongoing bias and discriminatory practices in American society in a general and by law enforcement officers in particular. In reaction, some people have called these athletes “unpatriotic”. In 1,000 words or fewer, describe your understanding of what it means to be a patriot, what kinds of behavior you think would be unpatriotic, and what forms of protest against discriminatory laws, customs, or patterns of behavior you would consider legitimate.

1st Place: The Ill-Considered Nature of Our Discussion of Patriotism

Henry Carter (Staples High School senior)Colin Kaepernick’s decision to kneel during the national anthem in August of 2016 understandably effectuated impassioned responses around the nation and reinvigorated the debate around racial inequality and police brutality in the United States. Though harsh invectives from right-wing pundits and politicians and praise from their left-wing counterparts reflected the deep cultural divisions emerging in the months before the presidential election, Kaepernick’s actions seemed at the time to be a possible turning point in race relations, compounded by momentum from the climax of the Black Lives Matter movement in 2015.

The national discourse that followed, however, was disappointing. What I, like many others, had perceived as a crucible for change fell into a recognizable pattern of political maneuvering which went frustratingly unnoticed and unchallenged by prominent activists against racial inequality and police brutality. The agenda set by GOP leaders maintained that these athletes would be judged solely by their fealty to American institutions that had oppressed them for hundreds of years, a dangerously misguided standard that not only denied their experiences as black people in the United States but distracted from the issues they were protesting in the first place. This faulty premise was implicitly accepted by proponents of the #takeaknee movement in their misplaced efforts to authenticate the “patriotism” of protesting athletes, facilitating a discussion that has been ultimately counterproductive and oblivious to the reality of African Americans in today’s society.

Since Kaepernick’s decision to take a knee, social media has been flooded with images such as the one retweeted by President Trump in January: a widow grieving at a military graveyard, with the caption “THIS IS WHY WE STAND.” This image and the hundreds of others like it disseminated around the internet capture the focal point of outrage from conservative leaders: the belief that the athletes who chose to kneel during the national anthem demonstrated serious disrespect for veterans and those currently serving in the military.

Though this sentiment is understandable, its logic is flawed. The military is, in the symbolic sense, inextricable from the country it fights for. In this way, any protest against a nation’s symbol, such as the Star-Spangled Banner, can be misconstrued as expressing disdain for those who sacrifice themselves for the safety of civilians. GOP leaders have taken advantage of this fact to center the national dialogue around the disrespect of veterans and invoke outrage from earnest Americans who deeply care about members of the military. This has allowed politicians to not only divert attention from the reasons for protest, but advance their own careers by equating their condemnation of protests to support for the military.

The liberal counter to this conservative judgement of protesting athletes has been a naive attempt to prove the patriotism of athletes. While this may seem like a worthy goal in the ongoing debate over taking a knee, it accepts the flawed premise that black athletes must demonstrate patriotism towards a nation that has denied them civil rights and liberties since its inception, misaligning proponents of taking a knee with the original intentions of these athletes and further distracting from the true issues at hand. The athletes who take a knee are not protesting institutions that exist within the United States; they are protesting fundamentally American institutions.

The unfortunate truth is that our country was built off the backs of slaves, and this legacy has continued throughout American history. Prosperity in the United States has always been dependant upon the disenfranchisement of black people. Thus, while it may be well-intentioned, by trying to authenticate the patriotism of black athletes, proponents of the protests endorse the mistaken belief that these athletes should be judged by such a standard. As the systematic decimation of black families and communities has been an integral part of the formation and destiny of the United States, it makes little sense to define black athletes by their “vigorous support for [their] country” (as patriotism is defined by the dictionary). Not to mention, those on the left who have argued for the patriotism of protesters have also exacerbated the diversion of attention by GOP leaders from the issues being protested, further stagnating progressive dialogue on these issues.

Though I do believe the athletes who have taken a knee acted patriotically, I also believe that’s the wrong question to ask. From slavery to convict leasing to Jim Crow to housing segregation to mass incarceration, the marginalization of African Americans has been interwoven into the fabric of our nation, and it is unfair and ignorant to measure their actions by their “vigorous support” for the United States. Unfortunately, our discourse now hinges on this point and it has critically shifted the conscience of the American public away from the pressing issues being protested, such as racial inequality and police brutality.

There is a reason our founding fathers did not make free speech protected by the first amendment conditional on the fact of it being patriotic. To do so would not only hinder progress in the U.S. but create an autocratic regime in which free speech would cease to exist at all. Why then, is the focus of journalistic endeavors on both the right and the left to debate the extent to which taking a knee during the national anthem is patriotic?

What began as a promising opportunity to address racial inequality in our nation has devolved into public reckoning on the character of protesters, the result of clever political maneuvering on the right and ignorance on the left. Hopefully, moving into the future, we will consider prioritize the validity of speech over its loyalty to current institutions and paradigms, such that we will be able to create a society in which everyone is ensured life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

2nd Place: The Patriotism of Protest

Melanie Lust (Staples High School junior)When I look at the American flag, I see a set of principles.

I see perhaps the most complex and unique history in the world. I see a small group of refugees, relentlessly persecuted by their own government, taking the ultimate risk and fleeing to an unknown land, somehow birthing a three-hundred year empire.

I see struggle. I see the first colonies during their first winter on the brink of collapse. I see eventual omnipresent British control. I see a bloody conflict for freedom, and only in its most pure and uncompromised form.

I see a rich and beautiful culture, native to the North American territory, slaughtered until it dwindled nearly out of existence.

But there is also triumph — the survival and sustainability of Jamestown, expansion into thirteen colonies, increasing establishment of more and more self-governing institutions to combat British oppression, and Washington’s climactic victory at Yorktown that won us the Revolutionary War.

I see togetherness and strength in the interminable battle for equality and stories of those who have never known peace. I see a nation slowly learning that acceptance should not only be mandated by law, but exalted morally and universally.

I see the bold red of hardship and valour, the plain white of candor, and an ever-changing constellation sewn into the deep blue field of vigilance and justice.

And what I see, more than anything, is a set of values designed to counter tyranny. Our American identity took centuries to develop, and it came first from immigrants, then from those bound by the crude chains of British oppression, then from the Founding Fathers who strove to create a society in which tyranny can never prevail again.

America is unique because its identity was not born from borders or geography or ethnic circumstance. There is no American ethnicity. To be an American, one needs only to believe in one principle: absolute liberty and justice for all.

This is what the American flag means to me, and this is why, each morning, I stand and recite the pledge. I have a profound respect for our history and values, and this is what makes me a patriot.

But any person who refers to themselves as a patriot — especially any person who passionately admires the Constitution, as I do — knows that the only truly unpatriotic act is one that hinders the freedoms and rights of others.

The right to protest and free speech is clearly detailed in the Constitution’s first amendment. The football players who choose to act on these basic rights are honoring the Constitution in the most explicit manner possible. By virtue of living in a country such as ours, a nation designed since its birth to contradict all facets of fascism, the mere act of speaking freely and protesting, no matter what the context, is patriotic.

The natural exceptions for acceptable forms of protest are any that prohibit other citizens from their ability to exercise their rights. But kneeling on a field does harm to no one; nor does burning an American flag, nor does sitting down during the pledge of allegiance, nor does wearing a black band on your arm to resist American involvement in Vietnam. Looting stores and rioting in the streets is one thing; generating discussion around controversy is another.

The cause of the protest has little to do with the protest’s legitimacy. As long as no harm is done and the freedom of others is not infringed upon, the protest is legitimate. The simple brilliance of kneeling during the national anthem is that it does nothing except draw much-needed attention to the prevalent issue of racial discrimination, and it raises awareness for a broad spectrum of racial problems in our society.

Racism is an issue that affects almost every person living in our country, but is rarely talked about, and even more rarely addressed in a manner conducive to change. While I personally believe that the national anthem and flag are not representative of our modern society or racism, individuals should still have the right to manipulate the occasion of their reverence for protest.

And so, no matter how much protest of the flag conflicts with my personal values, I am in no place to criticize the football players who take a knee on national television to bring attention to the cause they believe in most. No matter how much I disagree with these protesters’ interpretation of our nation’s ideals, I would be a hypocrite to disregard their basic right to thought and expression.

The primary guiding principle of our democracy, and thus the guiding principle of American history, is exertion of individual freedom that does not inhibit the individual freedoms of others. Just as protesters have the right to silently and effectively engage a global audience about modern discrimination and racism, critics from coaches to the President are allowed to voice opinions about the topic at hand and their means of protest. However, restrictive, non-verbal criticism — such as a mandate from the federal government prohibiting football players from kneeling — is unconstitutional.

Censoring opinions that have no physical, palpable impact on anyone is a step towards fascism. The Founding Fathers explicitly designed our nation to contradict all political instruments that would advance authoritarianism. The fact that protesters are able to express their opinions without censorship is an exact result of this design, and it perfectly encapsulates the beauty of a democratic society.

The struggle, the separation, the ceaseless and bloody wars for freedom, the oppression and liberation, all led up to the nation we know now. In fact, protest against any cause at all should be viewed as a blessing , not disrespect for the nature of our country. A protester is a perfect model of the Constitution’s vision; he/she is openly speaking his or her mind, in effect contradicting fascism; he/she is following in the steps of the protesters that created our country to begin with; he/she is a true patriot.

3rd Place: Patriots Exercise and Defend Essential Freedoms

Sophie Driscoll (Staples High School junior)True patriots demonstrate love for their country by exercising and protecting its core principles, even in the face of personal risks. Thus, the participants of the “take a knee” movement are patriots.

The “take a knee” movement was launched in 2016 by NFL quarterback Colin Kaepernick in response to numerous fatal shootings of African Americans by police officers. According to data collected by The Guardian, 266 black Americans were killed by police in 2016, with black males aged 15-34 nine times more likely to be killed by police than any other demographic. Initially, Kaepernick sat during the national anthem before an NFL game. When questioned by reporters, he explained that he was sitting to protest racial discrimination by police officers.

After former Green Beret and Seahawks player Nate Boyer told Kaepernick that it would be more respectful to those in the military to kneel rather than sit during the anthem, Kaepernick began to “”take a knee”,” i.e. kneel silently, during the national anthem. Since then, other athletes in the NFL and elsewhere have similarly taken a knee in protest of racial inequality. By leading this movement, Kaepernick has used his platform as a professional athlete to speak for the voiceless.

The “take a knee” movement should be categorized with the American Revolution, the civil rights movement, the women’s suffrage movement and other iconic protest movements as the quintessence of American patriotism. Like the “take a knee” movement, most of the protest movements that fostered important social change in this country were criticized in their day but are now thought of as a reflection of our most important values.

For example, a 1966 Gallup poll indicates that at that time nearly two-thirds of Americans had an unfavorable view of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. However, today, he is a revered civil rights hero honored with a national holiday. Similarly, although some people criticize Kaepernick’s protests against racial discrimination, it is likely that he will be more widely respected as a patriot in the future. Both the civil rights movement and the “take a knee” movement have exercised freedom of expression for the purpose of casting light on problems of racial discrimination that have plagued our nation throughout its history.